Greek myths retoldBy Michael Burke

The world economy is not strong and the President of the United States is sufficiently concerned about new shocks to it that he recently met the Greek Finance Minister to urge ‘flexibility on all sides’ in the negotiations between the Syriza-led government and its creditors. US concern is fully justified.

In any attempt to reach agreement it is important both to have an objective assessment of the situation and to understand the perspective of those on the opposite side of the table. In Mythology that blocks progress in Greece Martin Wolf, the chief economics commentator for the Financial Times argues that negotiations to date are dominated by myths. He demolishes some of these key myths in turn: that a Greek exit would make the Eurozone stronger, that it would make Greece stronger, that Greece caused the crisis driven by private sector lending, that there has been no effort by Greeks to repay these debts, that Greece has the capacity to repay them, and that defaulting on the debts necessarily entails leaving the Eurozone.

Together, these provide a useful corrective to the propaganda emanating from the Eurogroup of Finance Ministers and ECB Board members. Some if this is slanderous, in repeating myths about ‘lazy Greeks’ (who have among the longest working hours in Europe). Much of it is delusional, based on the notion that Greece can be forced to pay up, or forced out of the Euro without any negative consequences for the meandering European or the world economy.

Austerity ideology

The genuine belief in a false idea, or a demonstrably false system of ideas constitutes an ideology in the strict meaning of that word. Inconvenient facts are relegated in importance or distorted, and secondary or inconsequential matters are magnified. Logical contortions become the norm.

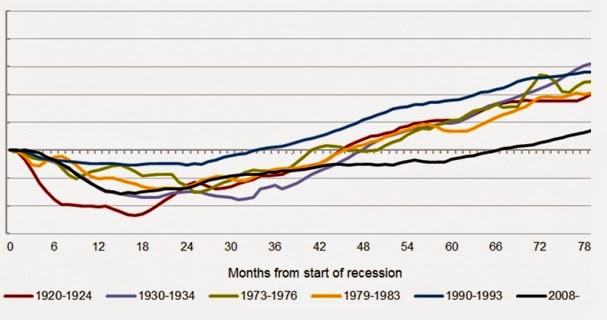

All these are prevalent in the dominant ideology in economics, which is supplemented by another key weapon, the helpful forecast. In Britain for example, supporters of austerity argued it would not hurt growth and the deficit would fall. Now there is finally a recovery of sorts, they argue austerity worked, ignoring all the preceding five years and the unsustainable nature of the current recovery (and the limited progress in reducing the deficit).

For Greece the much more severe austerity and its consequences means that supporters are still obliged to rely on the helpful forecast to support their case. The Martin Wolf piece includes a chart of IMF data on Greek government debt as a percentage of GDP, which is reproduced in Fig.1 below.

The IMF includes not only data recorded in previous years but its own projections for future years. From a government debt level of 176% of GDP in 2014, the IMF forecasts a fall to 174% this year and 171% in 2016 and much sharper declines in future years. The IMF has also forecast an imminent decline in Greek government debt ever since austerity was first imposed in 2010, which has not materialised.

Fig. 1 Greek Government Debt, % GDP & IMF Projections

However, the most recent data released by the Greek statistical service Elstat shows that Greek government debt rose once more (pdf) at the end of 2014 to stand at €317bn. The total debt was €9bn higher in 2014 than 2013, whereas the IMF forecast is effectively flat. Worse, as the Greek economy is still contracting the debt as a proportion of GDP will be rising sharply, not falling as officially projected.

In the course of 10 years the Greek government debt level has effectively doubled as a proportion of GDP close to 180%. Most of this took place while austerity was being implemented. The unavoidable verdict is that the debt burden is unstainable and that austerity will only increase it.

To date the Syriza-led government has met all its obligations to creditors but this clearly cannot go on for very long. It is possible that it may prefer to default on the ECB, which can in the end simply print the money (as with its Quantiative Easing programme, but from which it currently excludes Greece).

Defaulting on the IMF is perhaps more politically difficult, as its Board would have to convene a meeting of all shareholders. €3.46bn is due to the ECB on July 20.

But a default is necessary and inevitable. The authors of the Maastricht Treaty thought that anything more than debt level equal to 60% of GDP was dangerous. Then this would provide an appropriate target for Greek debt reduction.

Investment flows

In the Martin Wolf piece he also suggests that debt reduction should occur “after the completion of reforms”. This is mistaken. ‘Reform’ in the context of the negotiations is a synonym for deregulation, privatisation, attacks on workers’ rights and living standards. This has already been tried and failed. It is a myth that too many Greek regulations, or too much state ownership, or workers fighting for better pay and pensions is the cause of the crisis. All those were in place in 2003 and 2004 when real GDP in Greece grew by 6.6% and 5% respectively.

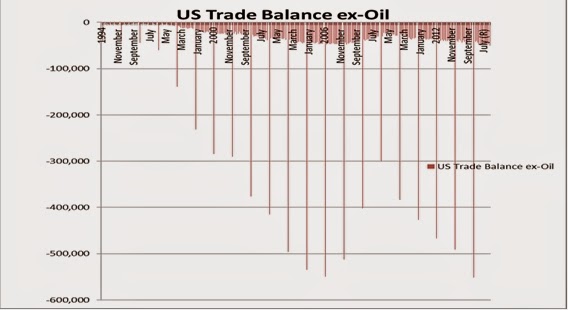

One myth that hardly needs to be dealt with any longer is that the crisis was caused by imbalances within the Eurozone current accounts (the balance of trade plus overseas interest payments). For a period this became a key explanation of the crisis (pdf) in the official ideology. It has been largely abandoned as all the crisis countries have swung into surpluses. Greece now has a current account surplus because imports have slumped and so remains in crisis.

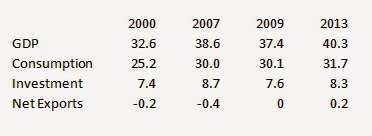

A common feature of the crisis countries is that they were beset by huge inflows of private sector capital seeking returns, primarily through speculation in property and housing. It was when these private sector inflows dried up and reversed that the crisis became apparent. Until austerity was imposed in 2010 the fall in Greek GDP due the recession was almost exactly the same as in Germany or in Britain, a fall of approximately 4.75% in all cases.

The austerity policy and the ratings’ agencies induced panic had the effect of driving capital flows back from the ‘periphery’ to the ‘core’ countries. Ferocious austerity in Greece and the other crisis countries meant that private sector banks withdrew capital and repatriated it to the key banking centres of Europe: Britain, German, the Netherlands and France.

These private sector speculative flows were destabilising in both directions. They caused both the boom and the bust in Greece and elsewhere. A solution based on reviving these flows, with the inducement of ‘reform’ can only end in renewed destabilisation and crisis. The desperation of these private sector investors is demonstrated by the fact that, for most industrialised countries currently (excepting Greece) borrowing rates are close to zero as unutilised capital seeks a return.

Structural adjustment

The Greek economy needs structural adjustment. For the ideologues of austerity this is a synonym for wage cuts. But Greek finance minister Yannis Varoufakis is right, cutting wages even further will have no effect on improving Greek competitiveness in key industries, “we are not going to be competitive with Mercedes-Benz and Toyota, simply because we don’t make cars.”

The structural adjustment needed is to increase the productive capacity of the Greek economy. This requires productive investment on a large scale. Prior to the crisis the EU did provide some transfers of funds for investment, as well as current transfers in the form of the Common Agriculture Policy and other funds (which is why the anti-austerity parties and most voters in the crisis countries are not anti-EU). However, these were on an insufficiently large scale and were in any event overwhelmed by the private sector inflows which were primarily directed towards construction and housing.

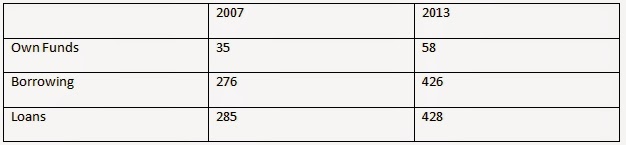

Worse, the EU has cut its funding for investment as the crisis has deepened. This has exacerbated the private sector withdrawal of capital and is an important factor in prolonging the crisis. Fig.2 below shows the levels of investment from the EU and the different forms of investment from the private sector, both total investment (Gross Fixed Capital Formation) and productive investment, which excludes housing.

This is a punitive measure and is entirely contradictory to the objective needs of the Greek economy. All properly functioning single currency areas require significant fiscal transfers in order to be sustainable. This follows from the fact that all regions or countries in a monetary union are subject to very similar monetary conditions (official interest rates, exchange rates, and so on) yet have very different levels of productivity. Those levels of productivity will diverge to a crisis point unless there are sufficient fiscal transfers to compensate. If the fiscal transfers are sufficiently large and well-directed, they can even compress or reverse the divergence in productivity. Currently, the policy of the Troika is to lay siege to the government in Athens in an attempt to starve it into submission.

As a result, the Greek economy is at that crisis point. It requires very large fiscal transfers otherwise it will diverge out of the Eurozone. This is in addition to the requirement for a very substantial debt write-off already noted. Even then, very strong government and supranational measures would be required to direct the inevitable revival of private sector investment that would inevitably follow a large increase in (supranational) public sector investment. The public sector must begin to direct large-scale investment.

Martin Wolf is quite right to attempt to disabuse the ideologues of austerity of their Greek myths. There is no prospect of an end to the crisis without very substantial debt reduction. It is also reckless bravado to claim that only Greece would be hit by a forced exit from the Euro. But even debt reduction is insufficient to end the crisis, and further ‘reforms’ would only deepen it. Very large fiscal transfers to pay for a structural upgrade of the Greek economy are necessary.

The biggest beneficiaries of the EU are the big firms and banks in the leading EU economies. They need to start paying for this benefit or they will lose it.

Recent Comments