Why China maintained its strong economic growth

By John Ross

Introduction

China’s GDP growth in the 1st quarter of 2019 was 6.4% – the same as in the last quarter of 2018. This figure, and other economic data released at the same time, refuted predictions of sharp economic downturn in China made in the Western media.

The Financial Times headline regarding the first quarter’s results was ‘China GDP grows faster than expected in first quarter’ – by which it meant faster than the FT had expected! The Wall Street Journal’s headline similarly was ‘China Growth Beats Expectations… Many economists prepared for a weaker first-quarter performance’ – by which it meant economists the Wall Street Journal had paid attention to had expected a weaker performance.

In reality, however, there was no need to anticipate any unacceptable slowing of China’s economy provided that current trends were correctly understood.

First, appropriate short-term stimulus measures had already been taken and are working their way through the economy.

A significant credit stimulus has been given. Bank lending was 1.7 trillion yuan ($254 billion) in March compared to 0.9 trillion ($135 billion) in February. Total social financing increased by 2.9 trillion yuan ($433 billion) in March compared to 0.7 trillion yuan ($105 billion) in February. The effect of this stimulus was shown in the good data for March – with an 8.5% increase in industrial production, the best since 2014, and an 8.7% increase in retail sales. Exports in March rose by 14.2% year on year in dollar terms.

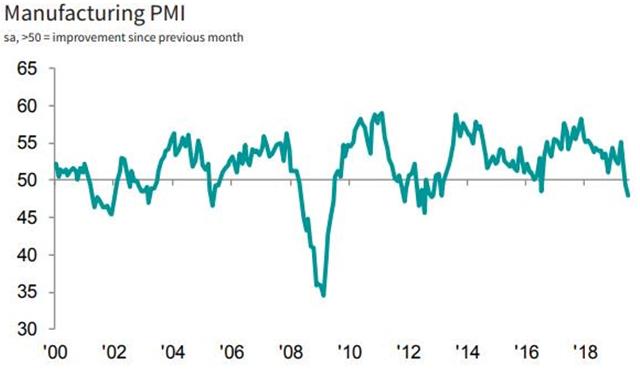

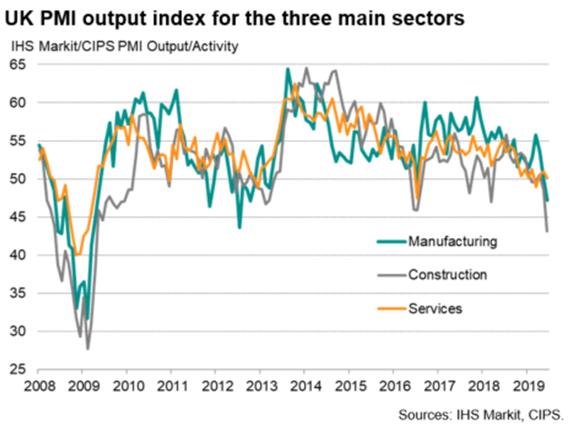

China’s official manufacturing PMI rose from 49.2 in February to 50.5 in March. The Caixin manufacturing PMI, more weighted towards smaller firms, rose from 49.9 in February to 50.8 in March. The official non-manufacturing PMI strengthened its expansion from 54.3 to 54.8.

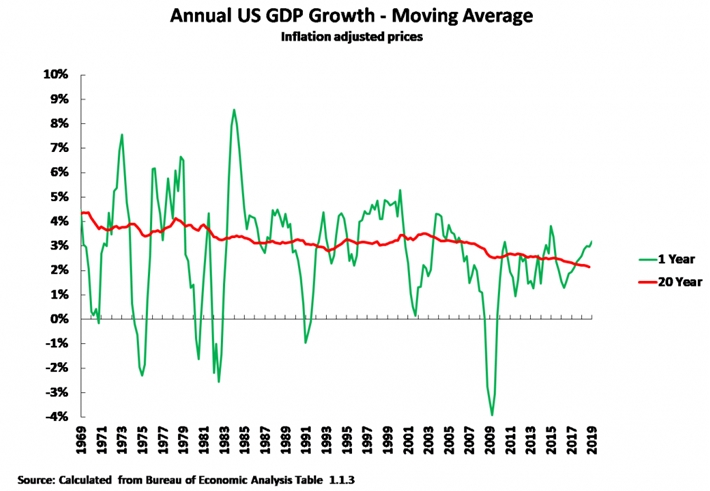

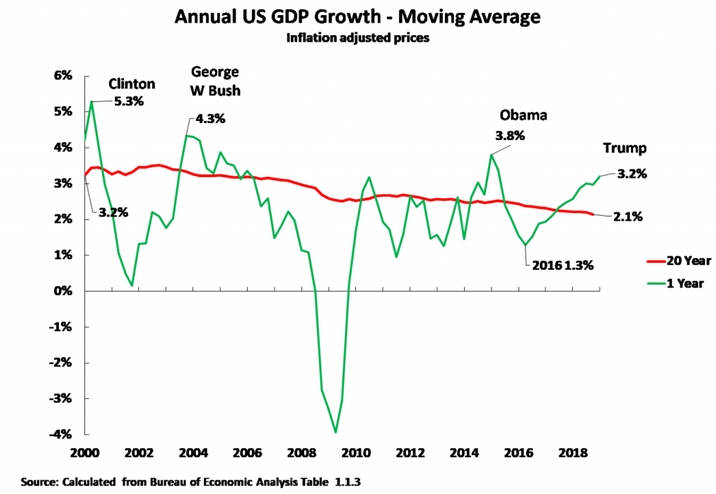

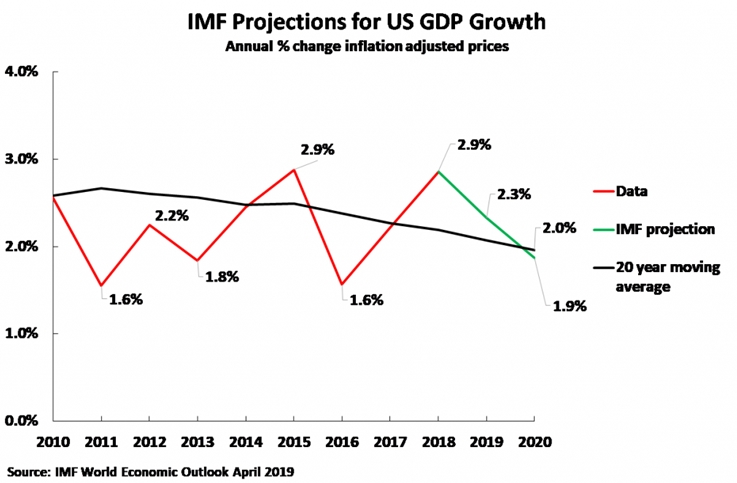

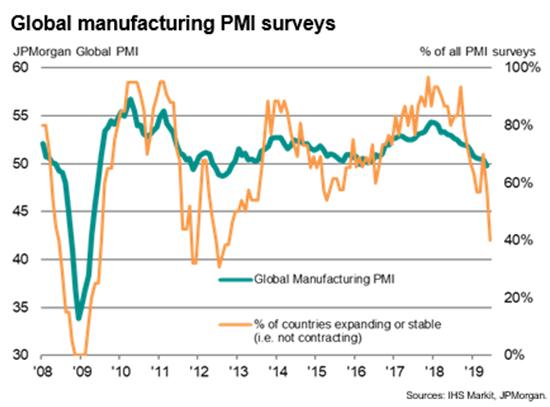

This strengthening data in March is particularly good in light of the international slowdown being predicted by the IMF and other international economic organisations.

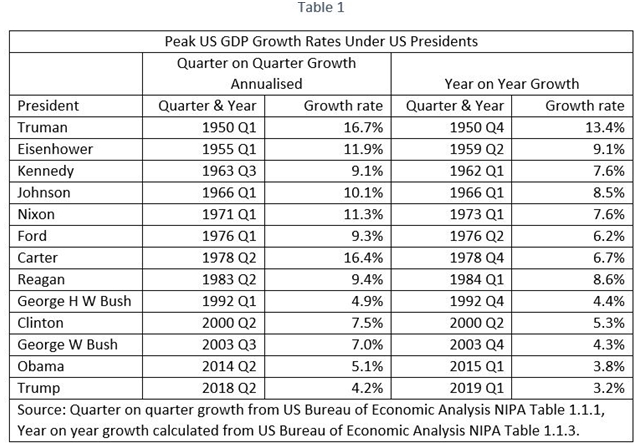

The IMF projects that GDP growth in the advanced economies as a whole will fall from 2.3% in 2018 to 1.8% in 2019. The slowdown in the largest Western economic centres is estimated to be even greater. The IMF projects that EU growth will fall from 2.1% in 2018 to 1.6% in 2019, a decline of 0.5%, and US growth will fall from 2.9% to 2.3% in the same period – a decline of 0.6%. As the growth rate of the Western economies is much slower than China this means that this slowdown in the US and EU is proportionately much greater compared to its starting point than in China.

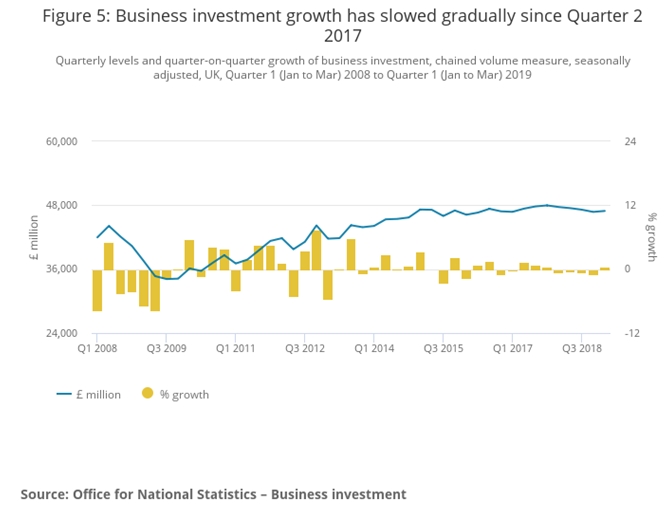

But in addition to these short-term trends in China’s economy what is even more important for the medium term was the turnaround in fixed investment. The rise in fixed asset investment was 6.3% year on year – up from 6.1% in the previous month and from a low point of 5.3% in August 2018.

The reason this is crucial is set out in the article below. It shows in a detailed way that it is investment, and not any other major factor in the economy, which controls China’s rate of economic growth – as it does in other major economies. In addition to its medium-term effect it was the fall in fixed investment which led to the economic slowdown in the second half of 2018, and the upturn which led to the good results in the first quarter of 2019 and in March in particular. Quantitative analysis of the data therefore confirms that it is fixed investment which is the most powerful factor in China’s medium-term economic development and its short-term macroeconomic regulation.

The article below was written before the publication of the first quarter 2019 economic data in order to analyse current US policy towards China and China’s economic slowdown during 2018. Its conclusion was clear ‘policies which affect capital inputs into China’s economy, that is investment’ have the most powerful effect in ‘lowering, sustaining or raising China’s economic growth rate.’ But the new economic data for the first quarter of 2019 strongly confirms the analysis of the article. The analysis in the article therefore deals with both short term and medium-term trends in China’s economy.

The economic context of current US policy towards China

US trade policy towards China has not only economic but directly geopolitical goals. The latter is to attempt to slow down China’s economic development to the point where this creates problems for the Communist Party of China (CPC). As the Wall Street Journal, put it, openly hoping for this result: ‘China’s economy is slowing, which could dent support for Communist Party leadership.’. This key journal of US hard liners expressed fear that in the China-US trade negotiations there was a danger of: ‘a deal that won’t lead to fundamental changes by China, including reducing the power of its state-owned enterprises.’ This latter goal, however, was a means to another end. As the Wall Street Journal summarised it in another article regarding the aims of US anti-China hardliners, they were: ‘focussed on steps forcing China to give ground on issues it sees as crucial to maintaining the Communist Party’s rule.’

The Washington Post, one of the most influential US political newspapers, put it similarly urging a hard-line: ‘One of the main points of contention in the protracted trade discussion has been the role of China’s state-owned enterprises.’ It noted: ‘Trump is demanding… a sweeping overhaul of China’s economy a key condition for ending the U.S.-China trade war…. Securing… assent to abandon the economic model that lifted China… to become the world’s fastest-growing major economy would crown Trump’s confrontational diplomacy with success.’ Its conclusion was the same hope as the Wall Street Journal, that economic policies could be imposed by the US on China which would weaken the position of the Communist Party: ‘Trump’s hopes of winning genuine structural changes in China’s economic model are colliding with…. preserving Communist Party control.’

This geopolitical goal, disguised as an economic one, is adopted because US anti-China forces accurately understand that the CPC is the core of the People’s Republic of China (PRC) and the rejuvenation of the Chinese nation. Therefore, anti-China forces believe that, in the same way that the overthrow of the CPSU led to the collapse of the USSR, and a historic geopolitical catastrophe for Russia, if they could weaken the CPC then they would be able to impose a similar historic defeat on China – blocking China’s national rejuvenation.

Under those circumstances, when an economic policy is being pursued with a geopolitical goal which is against the interests not only of China but of the world, it is therefore important that there is an accurate understanding of economic forces which are operating. China can no more escape economic laws than any other country. If there is an accurate understanding of the economic forces operating, there will therefore be the greatest ability to deal with any negative pressures from outside China. Equally, if there is a misunderstanding of the economic processes operating, rhetoric or effort will not be able to avoid the negative consequences.

Valuable articles by other economists have concentrated on questions such as demand management while the focus of this article is the medium/long term supply side of China’s economy. These two approaches are not contradictory – both demand and supply sides of the economy must be analysed, and demand measures may in an important number of cases be more rapid in their effect. It should simply be noted that in the medium/long term the supply side of the economy dominates and in the shorter-term demand measures must necessarily operate through creating changes on the supply side. That is, to produce changes in economic growth, demand must lead to changes in economic inputs – changes in demand which do not affect supply side inputs may produce inflation or deflation, but they do not produce changes in economic growth. Therefore, it is also necessary to analyse the supply side in order even to assess the impact of demand side measures. This article’s aim is to therefore to analyse in a quantified way the fundamental supply side forces operating in China’s economy.

China’s per capita GDP growth is the fastest of any major economy

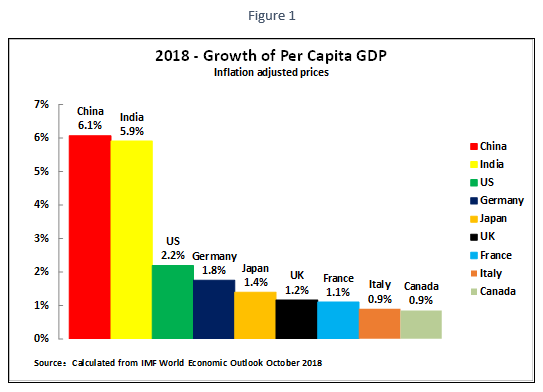

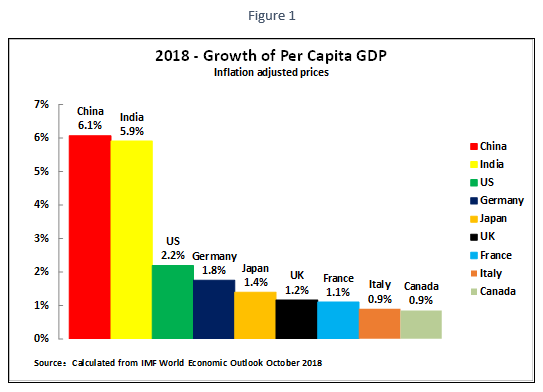

To avoid any misunderstanding in what follows, it is necessary to have a strictly balanced analysis of the situation of China’s economy. In 2018 China had the fastest per capita GDP growth of any major economy – a position it has held for decades. Figure 1 shows that on the IMF’s estimates China’s per capita GDP growth in 2018 was 6.1% compared to India’s 5.9%, 2.2% in the US, 1.8% in Germany and 1.4% in Japan. As analysed below the fact that China’s population growth is now significantly lower than India, the US, the UK, and Canada, to make comparisons simply among major and G7 economies, necessarily affects China’s ranking as measured by total GDP growth. But the well being of China’s population depends more on per capita GDP than on total GDP. To take one example, even if India’s official GDP figures are accepted, and they are not by many experts even in India, China’s per capita GDP growth is still faster than India’s – and China’s per capita GDP growth is almost three times as fast as the US, more than three times as fast as Germany, and more than four times as fast as Japan. Talk in the Western or Chinese media that China’s economy is in ‘deep crisis’ is therefore merely empty propaganda – as with similar claims made for decades. Furthermore there is no reason to believe that either in the short or medium term such a crisis will develop – China has the strongest macro-economic mechanisms in the world for preventing a severe economic slowdown, as analysed in my book 别误读中国经济 (‘Don’t Misunderstand China’s Economy’). The issues in this article therefore do not to deal with such non-existent ‘crises’ but primarily deal with clarifying medium/long term issues on which it is important to avoid conceptual or factual confusion.

Testing explanations of China’s economic slowing

There are currently three popular explanations of China’s economic slowing appearing in the media which are examined here against the test of facts.

- That the slowing of China’s economy is due to lack of proper market mechanisms, a claimed negative effect of SOEs in the economy etc.

- That China’s economic slowing is due to demographic factors, a slowing of the growth of the working age population followed by its slow decline.

- That China’s economic slowing is due to a decline in capital inputs.

These explanations, as will be seen, are not mutually exclusive. However even when more than one process is operating it is crucial to find out which are the most powerful – as only by dealing with the most important of these can an adequate policy response be developed.

The conclusions arrived at from study of the facts are clear:

- Demographic factors play some, but a small, role in the slowing of China’s economy.

- Factors such as inefficient market mechanisms, or SOEs play essentially an insignificant role in China’s economic slowing – although maintaining the efficiency of market mechanisms is crucial to prevent an excessive slowing of China’s economy.

- The overwhelmingly dominant factor in China’s economic slowing is the decline in capital creation and the fall in net fixed capital investment.

As these issues are crucial for China’s economic development this article examines these issues in a comprehensive way.

The necessity to use the most accurate data

To accurately analyse the processes operating in China’s economy it is vital to use real, and the most accurate possible, data. It is not unusual to see articles in parts of the media, which consists of ‘lists’ of issues without accurately analysing the real weight of each. It is indeed not unusual in parts of the media to see articles which contain no quantified data on trends in the economy but merely non-quantified claims. This is not merely wrong in principle but dangerous. Because by this method even if a real issue is pointed to, then if its real weight in the situation is not measured accurately this can lead to misleading judgements and consequences.

To explain this an analogy can be taken – comparing China’s economic development to a scientist analysing the path of a billiard ball across a flat table. If the scientist has ultra accurate measuring instruments it will be found that the trajectory of the ball is affected by innumerable forces – the gravity of the moon, the gravity of other planets, even the gravity of distant galaxies. The scientist is therefore stating something true if they say, for example: ‘I have found the trajectory of the billiard ball is affected by the gravity of the planet Mars.’ But, unfortunately, emphasising this true statement can lead to pseudo and misleading arguments. Because, if the scientist focuses only on the effect of Mars’s gravity on the billiard ball or says, ‘the trajectory of the ball is affected by the gravity of Mars, this is therefore the big issue to analyse’ or does not mention other forces, they are saying something fundamentally untrue – by far the most powerful force acting on the ball is the gravity of the planet Earth. Therefore, a statement which is true can be deeply misleading if its real weigh in the situation is not calculated.

This principle strongly applies to economic development. Innumerable factors affect economic growth, but it is necessary to accurately measure which are the most powerful and which less powerful. It was to accurately measure the weight of different factors in economic growth that the key tools of factual economic analysis were developed – growth accounting, national accounts statistics etc.

The practical consequences are obvious. If emphasis is placed on dealing with the less powerful factors in economic development, then even success in tackling these will not deal adequately with problems nor take advantage of economic opportunities. Only if the most powerful forces in economic development are dealt with can economic problems be solved, and opportunities successfully taken advantage of.

For this reason, this article concentrates on factually analysing the most powerful factors in the China’s economy – the policy implications are examined at the end of the article.

Growth accounting

The most accurate modern method to calculate the weight of different causes of economic growth is ‘growth accounting’ as originally developed by Robert Solow. Solow’s original formulation, however, suffered from two errors – it did not calculate the effect of changes in the quality of labour (education, training etc) and it did not calculate changes in the quality of capital (reflected in different rates of depreciation of capital). The necessary corrections to these measures were therefore subsequently introduced and adopted by the statistical services of the US, OECD and other international organisations.

Growth accounting analyses GDP growth in terms of three inputs – capital, labour, and total factor productivity (TFP). GDP is therefore:

GDP = capital inputs + labour inputs + TFP

TFP is defined as that part of GDP growth which cannot be explained by either capital or labour inputs.

Using a growth accounting framework, the real importance of popular explanations of the slowing of China’s economy can be easily factually analysed in terms of their effect on economic inputs.

- If the argument is accurate that slowing of China’s economy is due to lack of proper market mechanisms, a negative effect of SOEs etc., this would show in a slowing of TFP growth – as market efficiency, the existence of SOEs etc are issues of efficiency/productivity not issues of capital or labour inputs.

- If the argument that China’s economic slowing is due to demographic factors is accurate, i.e. due to negative shifts in the growth of working age population, this would be reflected in a slowing of labour inputs.

- If the explanation is correct that China’s economic slowing is due to a fall in investment this would be reflected in a decrease in capital inputs.

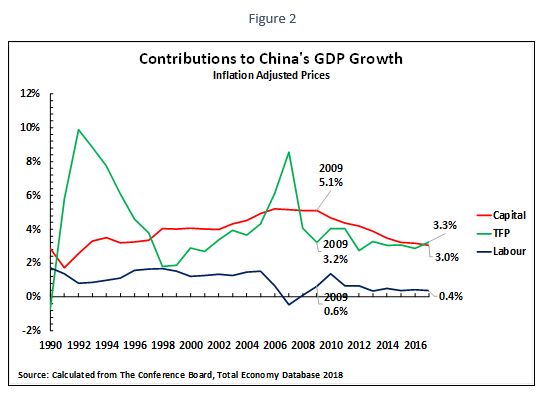

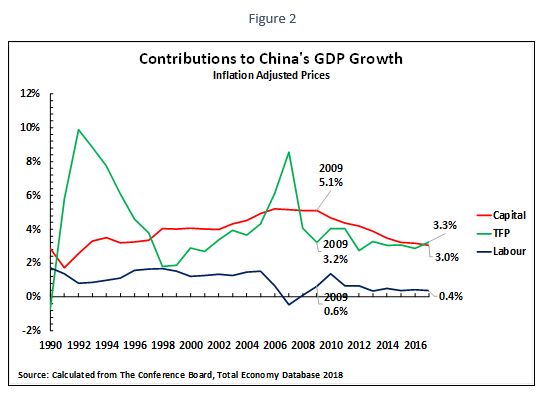

To analyse the factual situation regarding these inputs into China supply side, Figure 2 therefore shows the trends in China’s capital inputs, labour inputs, and TFP since 1990. As China’s response to the international financial crisis, and the framework for analysing the slowing of its economy, may be considered as starting in 2009 therefore the focus is comparing the situation in that year with the latest available data.

The key facts from growth accounting are clear. Between 2009 and 2017 China’s GDP growth fell by 2.3%. Breaking this down in detail:

- There was a small reduction in labour inputs, almost certainly primarily due to demographic factors, which diminished GDP growth by 0.2% a year. Calculated as proportion of the total slowing in China’s economy, 11.6% of the deceleration in GDP growth is due to the decline in labour inputs.

- There has been essentially no change in TFP growth – calculated to two decimal points TFP contributed 3.23% GDP growth in 2009 and 3.26% in 2017 (the increase from 3.2% to 3.3% in Figure 2 is merely due to a changing in the rounding of decimals).

- The reduction of capital inputs into China’s economy was from creating 5.1% GDP growth in 2009 to 3.0% GDP growth in 2017 – i.e. the fall in capital inputs reduced China’s GDP growth by 2.1%. The growth of GDP due to capital inputs fell by 41% between 2009 and 2017, accounting for 89.6% of the decline in GDP growth.

Therefore, evaluating the various popular theories regarding the slowdown in China’s GDP growth:

- The overwhelming factor in the fall in China’s GDP growth was the decline in capital inputs – which accounted for almost 90% of the decline in China’s GDP growth.

- There was a fall in labour inputs, primarily due to demographic factors, but this accounted for only slightly over 11% of the decline in China’s GDP growth.

- There was no significant change in China’s TFP growth – i.e. there is no evidence that the slowdown in China’s economy was primarily due to deterioration in market efficiency, or a negative role of SOEs, all of which would show up as a decline in TFP growth.

In summary, the overwhelming reason for the slowing of China’s GDP was a fall in capital inputs, which accounted for about nine tenths of the decline; there was a contribution from demographic factors, accounting for approximately one tenth of the fall in GDP, and there was no significant indication the slowdown was due to a decrease in market efficiency or the role of SOEs – which would show as a decline in TFP.

Fall in labour inputs- demography

Having examined the overall factual data, applying the famous Chinese dictum of ‘seek truth from facts’, the significance of the individual processes affecting the slowing of China’s economy may now be seen.

The first is that it is true that demographic factors play a role in China’s economic slowing – but it is a small one, accounting for only slightly over one tenth of the decline in the growth rate. Therefore, arguments that the slowing of China’s economy are primarily due to demographic factors, in the most extreme version that ‘China will get old before it gets rich’ will not withstand factual examination. As will be noted below this conclusion from growth accounting is fully confirmed by national accounts calculations – leaving no doubt as to the factual situation.

In terms of a precise analysis, it would theoretically be possible to maintain labour inputs even within existing demographic trends – this could be achieved by methods such as raising the retirement/pension age, by increasing the education and skill of the labour force etc. However, these would either involve very major social changes, e.g. the retirement/pension age is extremely sensitive in all countries, or it would require very large expenditures – for example, in expanding the education and training system. Some measures in these fields are therefore to be anticipated but it is improbable that these could fully offset demographic trends.

Therefore, it is accurate to state that some slowing of China’s growth rate due to demographic factors will occur. But the factual data shows that this has been a relatively small factor in China’s economic slowing. Claims such as that ‘China will get old before it gets rich’ are highly exaggerated as the facts show that trends in labour inputs/demography account for only a small proportion of China’s economic slowdown.

A relevant conclusion from demographic trends, however, is that slow growth of China’s population confirms that the most relevant criteria for measuring China’s comparative economic development is per capita GDP. China’s 0.5% population growth in 2018, is significantly slower than India’s 1.3% or the US’s 0.7%. But the economic wellbeing of China’s population is more directly related to per capita GDP than to total GDP. Data showing that China has the most rapid per capita GDP growth of any major economy was given at the beginning of this article.

TFP

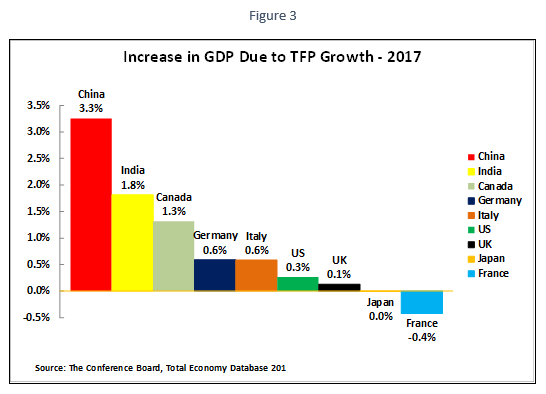

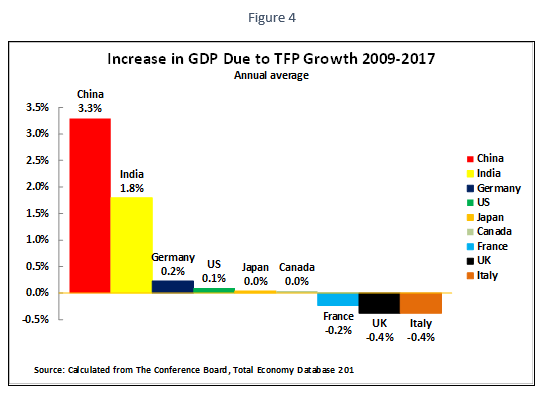

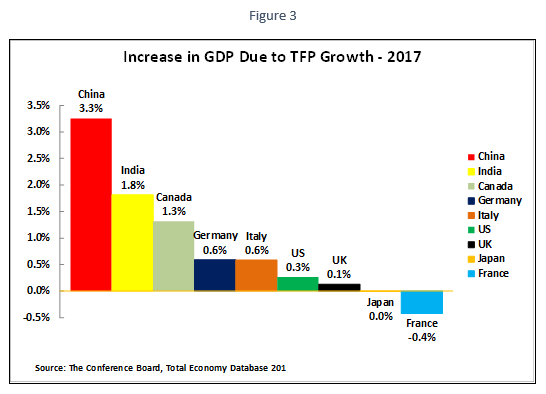

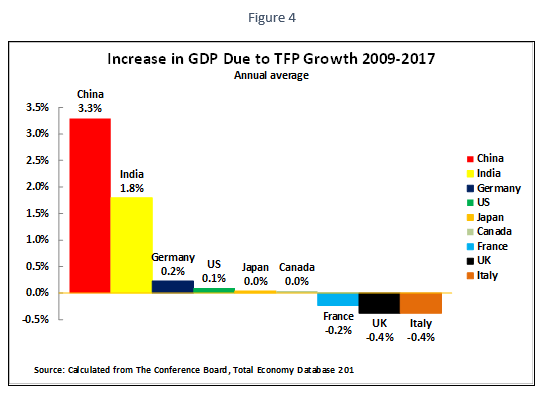

The application of up to date internationally approved methods of measuring the causes of economic growth, as noted above, shows clearly that it is a decline in capital inputs which is primarily responsible for the slowing of China’s economic growth – and not factors such as the role of SOEs or lack of market efficiency. Nevertheless, this does not mean that factors which affect TFP are not significant. Indeed, one of the reasons for China’s extremely rapid per capita GDP growth is its very rapid growth of TFP – by far the fastest for any major economy. Figure 3 shows that in 2017, the latest year for which there is data, China’s increase in GDP due to TFP growth was 3.3% compared to 1.8% in India, 1.3% in Canada, and 0.6% in Germany – the equivalent figure in the US was only 0.3%.

To confirm that China’s rapid TFP growth was not merely due to the specific situation in 2017, Figure 4 shows the annual average increase in GDP due to TFP growth for the major economies for the period 2009-2017. This shows no difference to the figure for 2017 for China of 3.3% and India at 1.8%. But the TFP growth in the G7 economies in this period was far lower – only 0.2% in Germany and 0.1% in the US, while in three G7 countries TFP growth was actually negative.

Numerous implications flow from these international comparisons. But one of the most important is that it is unrealistic to believe that China can accelerate its GDP growth by increasing its rate of TFP growth. On the contrary, China’s rate of TFP growth is so much higher than other major economies that it will take considerable effort to prevent China’s rate of TFP growth falling, with negative consequences for its overall economic growth rate. However, as the relation of TFP growth and economic growth is misunderstood in parts of China’s media, and it is suggested that a policy attempting to increase TFP growth is an alternative to one based on maintaining capital inputs, this issue will be examined in detail.

TFP growth is pro-cyclicalAnalysing the slower TFP growth in the G7 economies during the period 2009-2017, compared to the sustained TFP growth in China and India, relates to a feature of TFP growth which is crucial for China. It is sometimes suggested in sections of the media that China should follow a strategy of slower GDP growth in order to focus on increasing TFP. There are several errors in such a concept, but one of the most significant is that it simply will not work practically because international studies, and analysis of China, show that TFP growth is ‘pro-cyclical’ – i.e. faster GDP growth leads to faster TFP growth while slower GDP growth leads to slower TFP growth.

This situation is clear from both international comparisons and data for China itself. The OECD publishes regular systematic international comparisons of TFP growth, all of which confirm that TFP is ‘pro-cyclical’ – i.e. TFP growth increases when the economy is speeding up and TFP growth declines when the economy is slowing down. Therefore, slowing China’s economy would be expected to lead to slower TFP growth not faster.

The OECD uses the term Multi-Factor Productivity (MFP), instead of the term TFP utilises by Solow and other creators of economic growth accounting, but the concept is identical. The conclusion of the OECD in its Latest 2018 report is unequivocal: ‘multifactor productivity growth (MFP) behaves cyclically, i.e. it increases in upturns and declines in downturns… The empirical evidence confirms the cyclical pattern of MFP. In fact, MFP follows GDP growth very closely, not only in terms of direction but also in terms of the size of the change.’ This confirms the finding of all previous OECD studies – as shown in the appendix to this article.

One reason some writing in the media has failed to note this ‘pro-cyclical’ behaviour of TFP is that it erroneously believes TFP represents ‘technological change’ – which would not be expected to show a cyclical behaviour. But such a view is a misunderstanding of what TFP measures. As the OECD notes in the 2017 edition: ‘After computing the contributions of labour and capital inputs to output growth, the so‐called multifactor productivity can be derived. It measures the residual growth that cannot be explained by changes in labour and capital inputs and represents the efficiency of the combined use of labour and capital in the production process. Multifactor productivity is often perceived as a pure measure of technical change, but, in practice, it should be interpreted in a broader sense… Changes in multifactor productivity reflect also the effects of changes in management practices, brand names, organisational change, general knowledge, network effects, spillovers from one production factor to another, adjustment costs, economies of scale, the effects of imperfect competition and measurement errors.’

TFP growth in China

It follows from these general international comparisons that allowing slowing of China’s economic growth will be accompanied by slowing TFP growth. But it is, of course, also necessary to check that this general international finding also applies to China.

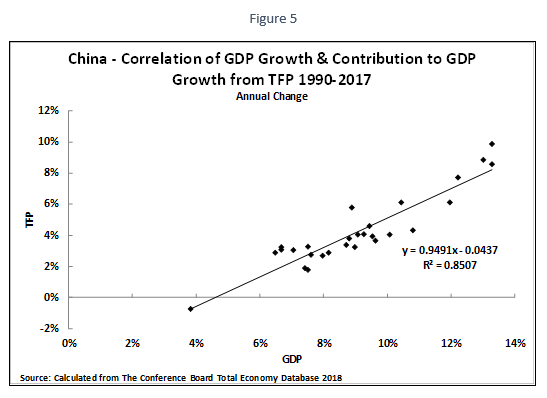

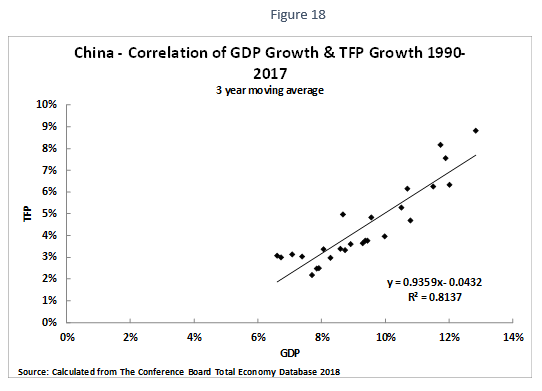

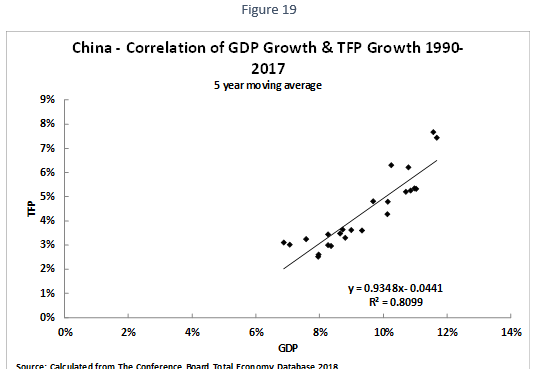

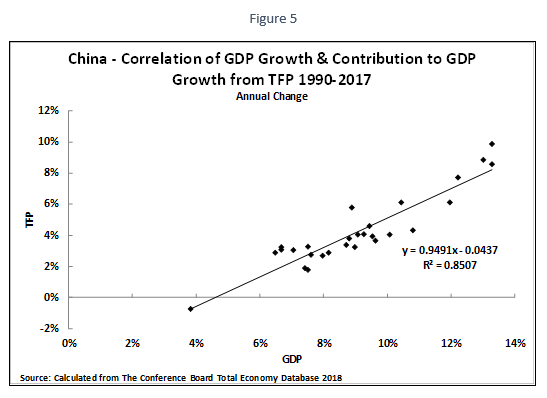

Analysis of the correlation of TFP growth and GDP growth in China confirms that it is fully in line with the international findings of the OECD given above – i.e. the speeding up of GDP growth is correlated with increasing TFP growth, and a slowing GDP growth is correlated with slowing TFP growth.

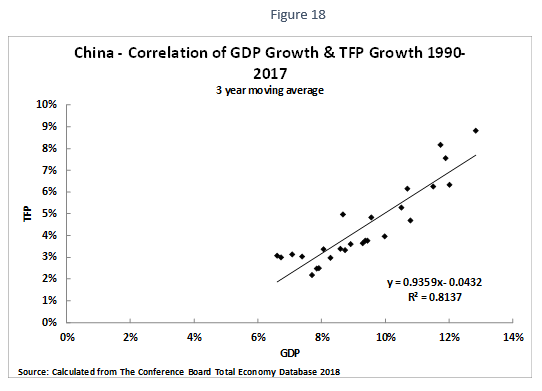

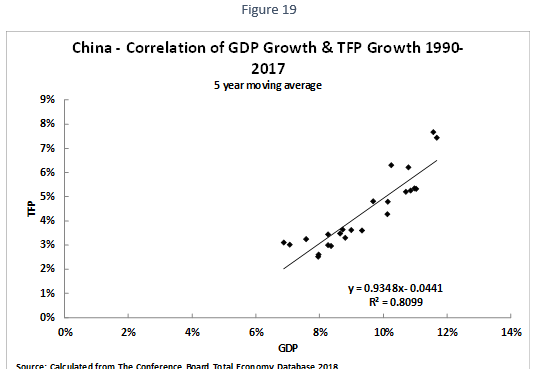

Figure 5 shows the annual correlation between China’s annual GDP growth. This correlation, of 0.85 is extraordinarily high and fully in line with the OECD’s international conclusions. To cross check that this correlation is not due to purely short term factors, in the appendix to this article Figure 18 shows the correlation of China’s GDP growth with TFP growth using a three year moving average, and Figure 19 uses a five year moving average. The correlations shown, 0.81 in both cases, are also extraordinarily high. The conclusions of this are therefore clear. There is nothing unusual in China’s economic development – it is in line with international data. As with other countries its TFP growth is pro-cyclical. Therefore, any policy based on slowing China’s economy to attempt to accelerate TFP growth will not work as this will exert downward pressure on China’s TFP growth. On the contrary, it follows from the pro-cyclical character of TFP growth that it is an upturn, an acceleration in China’s economic growth, that aids increased TFP growth.

It may, of course, be noted that correlation is not the same as causation. The fact that fast GDP growth is correlated with fast TFP growth does not prove that fast GDP growth causes fast TFP growth, or that fast TFP growth causes fast GDP growth, or that some other factor(s) causes both fast GDP growth and fast TFP growth. But for present purposes it should be noted that it is unnecessary to establish the direction of causation. It is merely necessary to note that the correlation of the speed of GDP growth and of the rate of increase of TFP is over 80%. Such a high correlation means that faster TFP growth cannot be achieved without faster GDP growth.

Therefore, the perspective that there can be fast TFP growth without fast GDP growth is unrealistic – whether considered from the point of view of international comparisons, as studied by the OECD, or whether considered in the specific case of China. Even less realistic is the idea that TFP growth can be accelerated while GDP growth slows.

It should be clearly noted from this that it does not follow that slower GDP growth may not help in achieving other ‘quality’ targets. For example, China has achieved notable success in environmental improvements, in lowering pollution and reducing energy consumption per unit of GDP. Achieving these targets may be achieved through slower GDP growth. However, it is clear from both international comparisons and the experience of China that slower GDP growth will not aid in achieving high TFP growth. On the contrary both international experience and that of China shows slow GDP growth will lead to slower TFP growth.

Alternative estimates of growth inputs

It should be noted that the above data uses China’s official calculation of its growth rate. Attempts are sometimes made in the West to claim that China’s real GDP growth is systematically exaggerated and in reality is far lower than the official data – although top Western experts who have examined this such as Tom Orlik, whose Understanding China’s Economic Indicators is the most thorough study of China’s economic statistics, do not agree with this assessment. Most such Western claims are unsystematic and such methods therefore cannot be used to thoroughly examine China’s growth. However, one systematic attempt to examine China’s growth using modern growth accounting methods, with a claim that China’s growth is much slower than its official data, has been made – by Harry X. Wu of the Institute of Economic Research, Hitotsubashi University, Tokyo. This claims that between 2009 and 2017 China’s annual GDP growth fell from 7.9% to 3.7%. But this also finds that the overwhelming reason for this claimed slowdown was due to decline in capital inputs. Wu’s calculations show that between 2009 and 2017 annual GDP growth due to labour inputs fell by 0.1%, annual GDP growth due to TFP fell by 0.1%, but annual GDP growth due to capital inputs declined by 3.9%.

Therefore, even if it is claimed that China’s GDP growth is lower than official data, use of modern growth accounting data shows that the overwhelming reason for the slowdown in China’s economy is not due to changes in TFP or demography but due to a decline in capital inputs.

National accounts data

So far modern growth accounting data has been used for analysis – growth accounting is necessary if TFP is to be calculated. This showed that the overwhelming reason for the slowing of China’s economy is the decline in capital inputs. However, while growth accounting is the most accurate method of calculating contributions to changes in GDP there are strong reasons for cross checking the results with other statistical data:

- If other data, for example national accounts statistics, corroborate the findings of growth accounting this would strongly confirm the certainty of the findings.

- Growth accounting requires a great deal of data for computation. There is therefore a delay in such data becoming available – such data for China is only available to 2017. More data for China is, however, available from other statistical sources.

As other such data is less accurate than growth accounting, if changes that other statistics demonstrated were small in scale, or contradicted growth accounting data, then it might create difficulties to interpret the results. Fortunately for present purposes, however, examination of national accounts and other statistics shows trends which are not small in scale and are fully in line with growth accounts data – they therefore confirm the findings of growth accounting. Such confirmation of trends by two different statistical methods, of course, strengthens confidence in the findings. Therefore, in order to evaluate the impact of changes other statistical sources will also be considered

The limited effect of demographic changes

The first trend which is confirmed by use of statistical sources other than growth accounting data is the negative but relatively small effect of demographic changes.

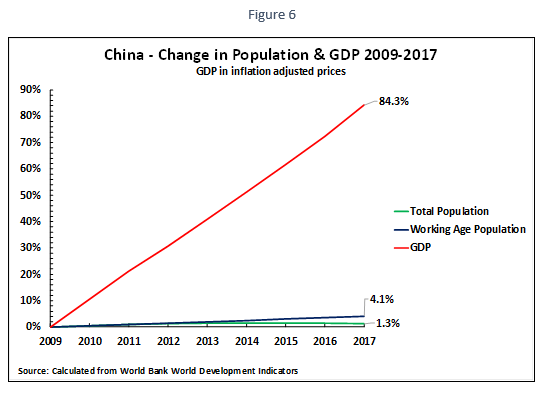

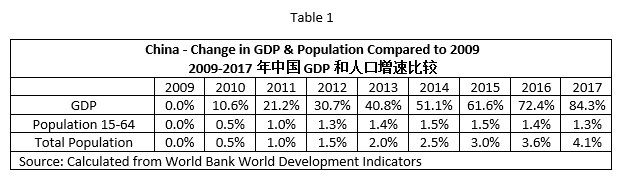

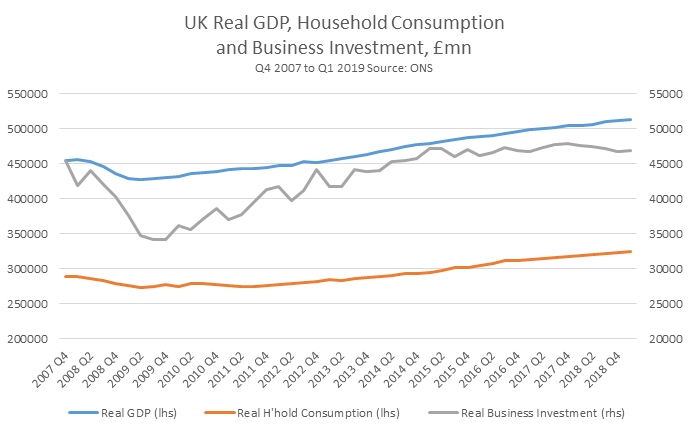

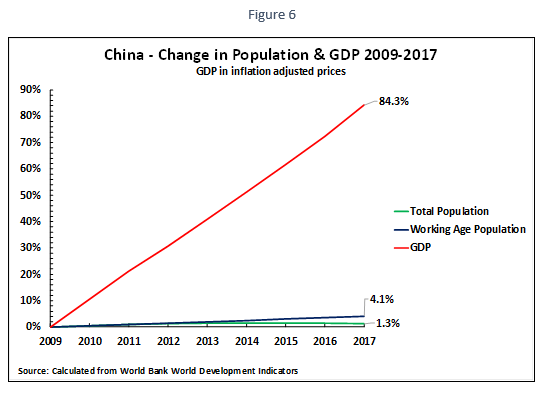

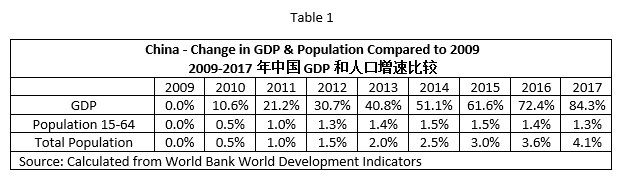

It was already noted that China’s retirement/pension age is very low by international standards – which represents a policy/social choice. The international definition of working age population is 15-64 years. By this criteria Figure 6 and Table 1 show that between 2009 and 2017, the latest available data, China’s internationally defined working age population rose by only 1.3%, and China’s total population rose by 4.1%, whereas China’s GDP rose by 84.3%. China’s GDP therefore rose 66 times as fast as China’s working age population and 20 times as fast as China’s total population.

In summary, China’s population increase played a negative but small role in China’s GDP growth. Similarly, therefore, the decline in China’s working age population, which reached a peak in 2015 at 1.5% above its 2009 level and by 2017 had fallen to 1.3% above its 2009 level, will play only a small role in slowing of China’s economic growth. The conclusion of growth accounting data is therefore confirmed by other sources. Demographic factors will play a negative role in China’s GDP growth, but this effect will be small. Claims such as ‘China will grow old before it grows rich’ are based on gross exaggerations and have no serious factual basis. The primary source of any slowing of China’s GDP slowing must therefore be sought in entirely different factors than demographic ones. The fact that both growth accounting and other data leads to exactly the same conclusion leaves no doubt as to the factual situation.

Fall in Net Capital Creation

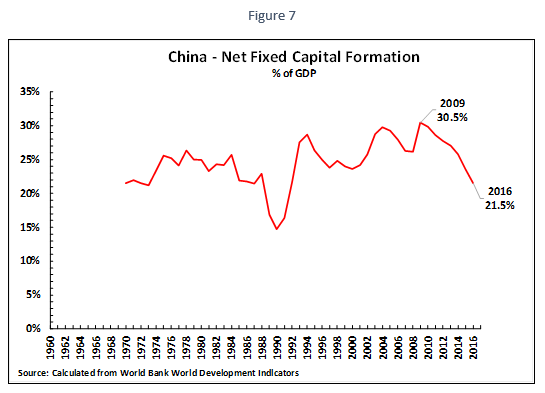

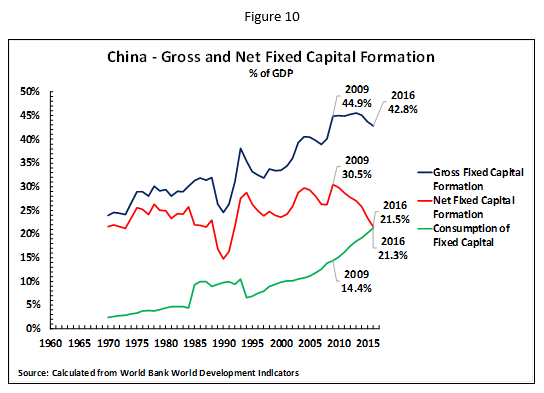

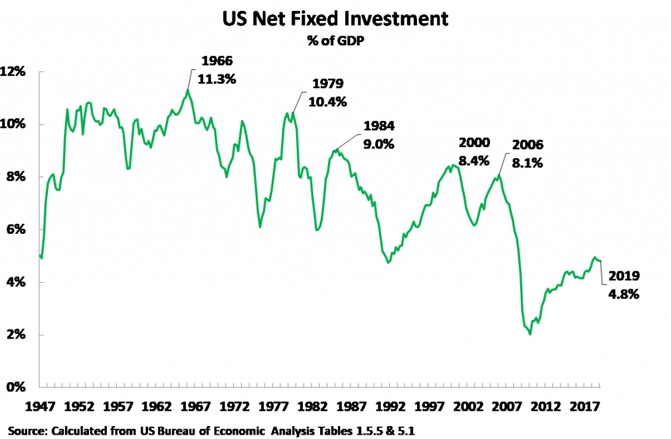

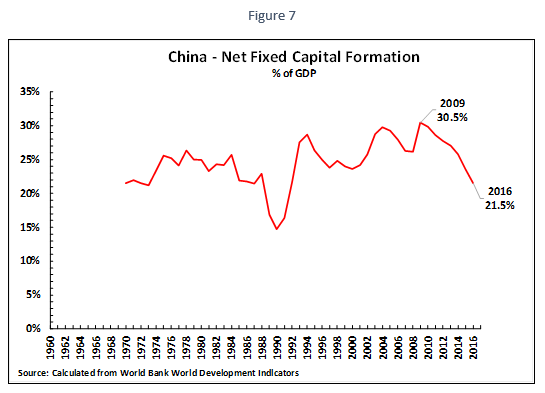

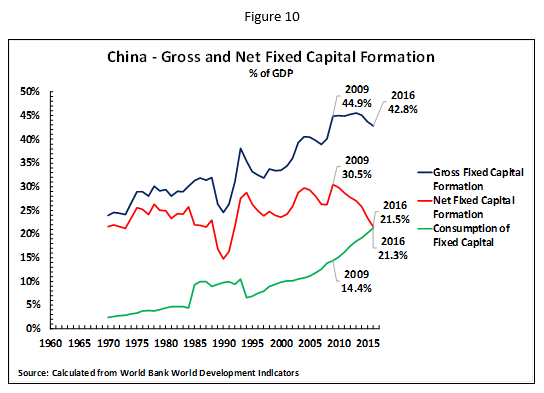

Turning to capital inputs, national accounts data fully confirms the fall in China’s capital inputs shown by growth accounting. Figure 7 shows that China’s net fixed capital creation (i.e. gross fixed capital formation minus depreciation) fell from 30.5% of GDP in 2009 to of 21.5% of GDP in 2016 (the latest available internationally comparable data) – this is a very large 9.0% of GDP fall.

Indeed, at a first approximation the relation between the reduction in China’s net investment and the slowing of the economy is even rather mechanical. In 2009-2016 China’s annual GDP increase fell from 9.4% to 6.7%. This is a reduction of 29% compared to the initial figure, while net fixed capital formation fell from 30.5% of GDP to 21.5% – a reduction of 29% compared to the initial figure.

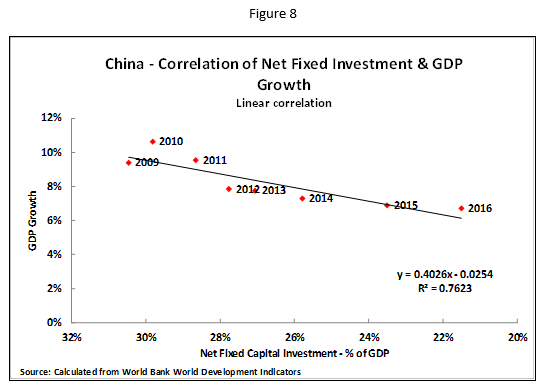

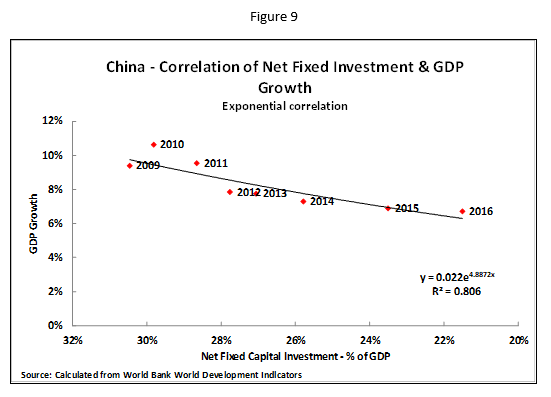

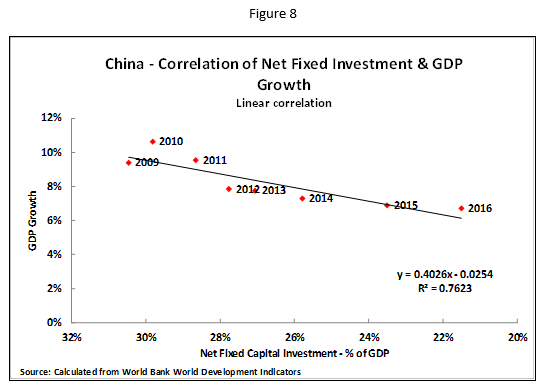

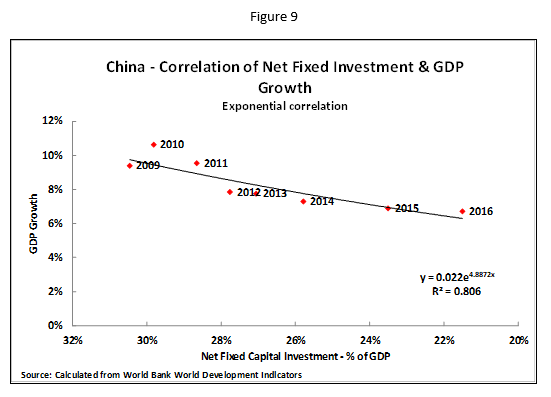

Figure 8 fully confirms the extreme closeness of the correlation between the decline in China’s net fixed capital formation and the slowing in GDP since 2009. The linear correlation is 0.76, by itself extremely high. However, there is no necessity for a correlation to be linear and Figure 9 shows that the non-linear correlation is 0.81 – extraordinarily high.

The usual caveat that correlation by itself does not establish causation is irrelevant here, as the extremely high correlation shows that it is not possible to increase China’s GDP growth without increasing the percentage of net fixed capital formation in GDP – and that any decline in the percentage of China’s net fixed investment in GDP will be accompanied by an economic slowdown. The extremely close correlation between net fixed investment and economic growth shown by the national accounts data is therefore fully in line with growth accounting calculations analysed earlier. Capital inputs are overwhelmingly strongly correlated with China’s economic growth.

Gross capital formation and depreciation

If the reason for this sharp fall in China’s net capital formation is now analysed further Figure 10 shows this is due to two processes. On World Bank data:

- Approximately one quarter, 24%, of the fall in the proportion of net fixed capital formation in China’s GDP is due to the decline in the percentage of China’s GDP devoted to gross fixed investment – which dropped from 44.9% of GDP in 2009 to 42.8% of GDP in 2016.

- Approximately three quarters, 76%, of the fall in the proportion of net fixed capital formation in China’s GDP is due to a rise in fixed capital consumption (depreciation) in China’s GDP. This is strongly affected by the rise China’s capital stock – capital consumption as a percentage of China’s GDP rose from 14.4% of GDP in 2009 to 21.3 of GDP in 2016.

It should be noted that an increase in consumption of fixed capital/depreciation in GDP is a normal process resulting from an increase in and modernisation of capital stock – it also occurs in the US. However, the increase in the percentage of GDP ascribed to capital consumption/depreciation in China is extremely high in terms of international comparisons. It would therefore be important for studies to be carried out to see if this figure is accurate or exaggerated. Nevertheless, the present data is so high that it indicates that capital consumption/depreciation is a significant factor in China fall in net capital creation – making it important to analyse net fixed capital creation and not only gross investment.

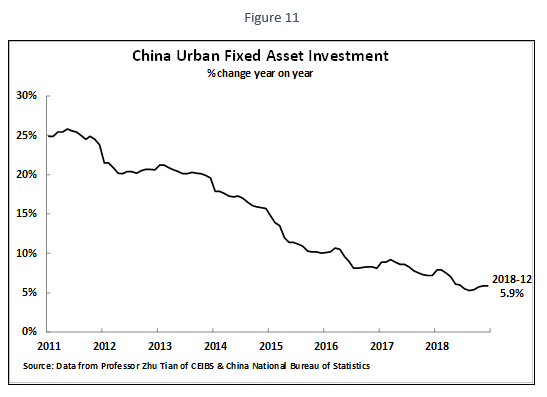

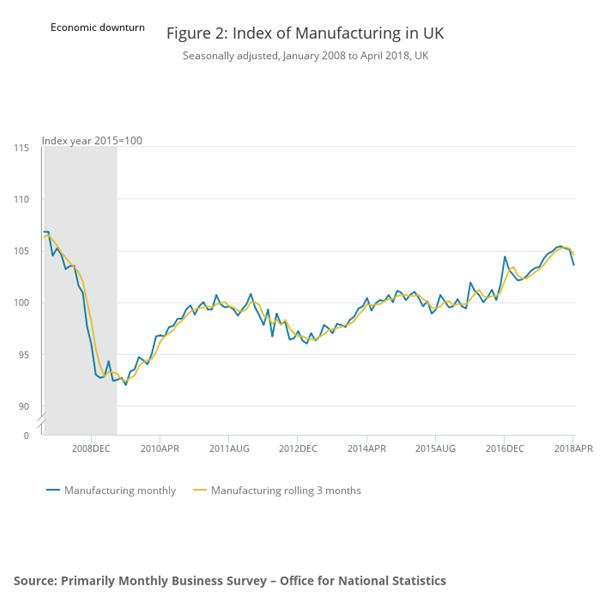

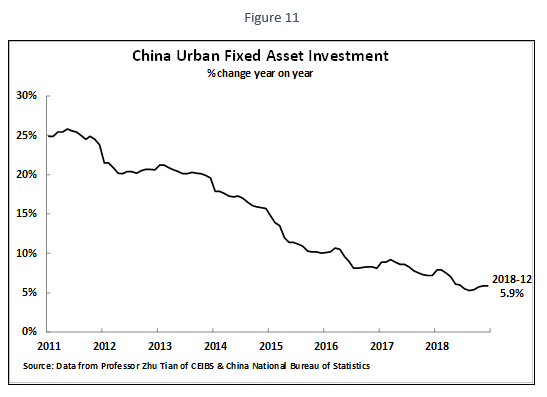

The most recent trends in fixed investment

Data for China’s gross fixed capital formation using national accounts data is available to 2017, and for net capital formation to 2016. However, data for 2018 for these categories will not be available for some time. Nevertheless for 2018 statistics for year on year changes in urban fixed asset investment leave no doubt that the same trend has continued. Figure 11 shows that the annual increase in China’s fixed asset investment fell from 7.2% in December 2017, and 8.1% in December 2016, to 5.9% in December 2018. As this latest figure is significantly below China’s growth of GDP at current prices in 2018 it is extremely likely that the percentage of fixed investment in China’s GDP declined in 2018 – continuing the trends in a fall in capital inputs shown in national accounts data. This trend then turned around in the first quarter of 2019, with a rise to a 6.3% year on year increase in fixed investment. Underpinning the improved economic trends in that period.

Saving

Turning from changes in fixed investment to overall trends in China’s capital creation/saving, which is necessary to finance investment, the same trends can be seen – only in an even more extreme form. It should be noted for clarity that throughout this article by ‘saving’ is meant China’s total savings – the sum of household saving, corporate saving, and government saving – and is not only household saving.

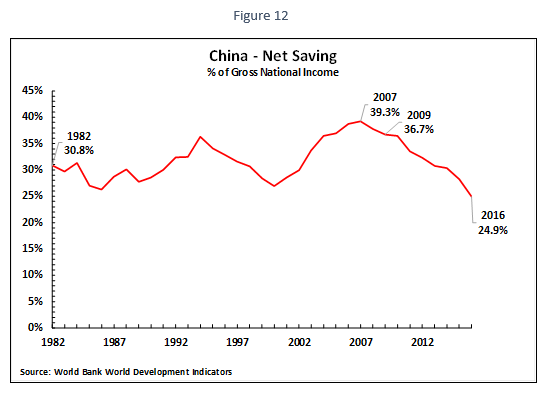

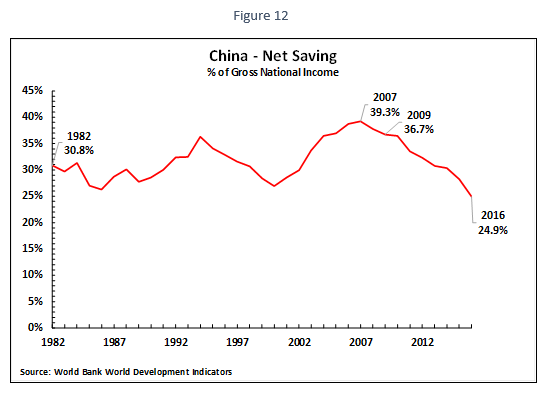

Figure 12 shows that China’s net saving, which is equivalent to China’s net capital creation, fell from a peak of 39.3% of Gross National Income (GNI) in 2007, to 36.7% of GNI in 2009, to 24.9% of GNI in 2016 – i.e. a decline of 11.8% of GNI in 2009-2016, and 14.4% of GNI in 2007-2016. This extremely large fall in the percentage of net saving in China’s economy, a large decline in the capital supply, is necessarily a strongly negative supply side shock for China’s economy.

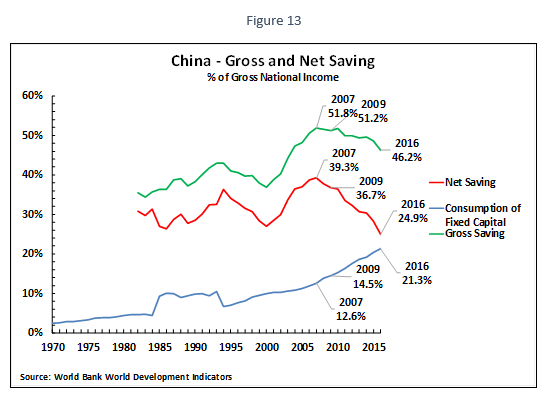

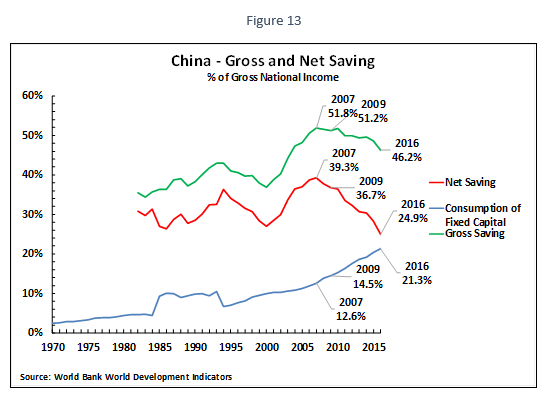

Analysing in greater detail this major fall in China’s net saving, i.e. net capital inputs, again shows this is due to two processes:

- China’s gross saving fell from 51.2% of GNI in 2009, and a peak of 51.8% of GNI in 2007, to 46.2% of GNI in 2016. This accounted for 42% of the fall in China’s net saving between 2009 and 2017.

- Capital consumption has risen from 14.5% of GNI in 2009, and 12.4% of GNI in 2007, to 21.3% of GNI in 2016. This accounted for 58% of the fall in China’s net saving between 2009 and 2017.

As already noted, estimates of savings/capital consumption are difficult to calculate but the changes shown are so large as to leave no doubt as to the general trend. There has been a sharp reduction in the proportion of China’s economy devoted to net capital creation.

This measured trend, paralleling the decline in capital inputs measured by growth accounting, is equivalent to a severe negative supply side shock to the economy. It is as though the petrol was drained out of the fuel tank of a car, making it inevitable that the car will not run for the same distance as before. Anyone expressing surprise that the car will not run as far as before is simply going against the laws of physics. Put in economic terms what has occurred is a reduction in the capital supply to China’s economy which is clearly confirmed by both growth accounting and national accounts data. As capital is one of the key inputs to the economy, such a reduction will necessarily produce economic slowing.

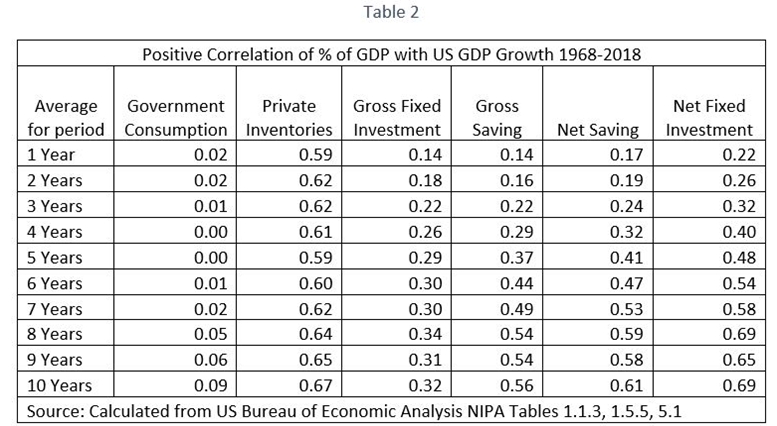

The correlation of China’s saving and economic growth

It was earlier shown that the correlation between China’s net fixed investment and its rate of GDP growth was extremely high. Net fixed investment is that part of China’s capital creation used for increases in fixed investment/capital stock in China. However, while fixed investment accounts for by far the largest part of use of China’s savings (gross fixed investment is approximately nine tenths of the use of China’s capital creation) small parts are used for other purposes – accumulation of inventories or as the surplus in China’s balance of payments. Therefore, for exactitude it is important to also study the correlation between China’s total capital creation/saving and GDP growth.

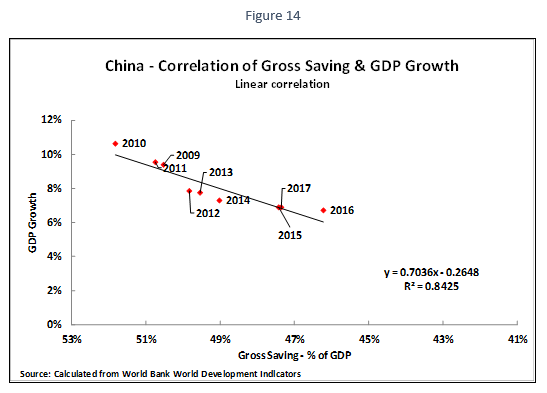

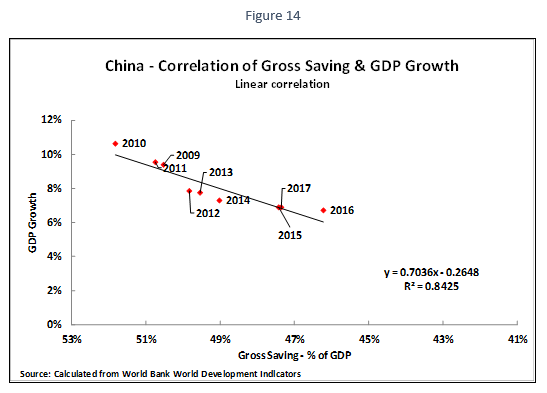

Such analysis is extremely revealing. It shows that the correlation between China’s capital creation/saving and its economic growth is even closer than between net fixed investment and economic growth. Furthermore, there is an extremely strong correlation between China’s gross savings and its GDP growth – whereas the correlation between China’s gross fixed investment and economic growth is low. This is statistically highly useful as it avoids the issue noted above that the calculated consumption of fixed capital/depreciation in China is very high compared to other countries. The fact that an extremely strong correlation of China’s gross capital creation/saving with GDP growth exists, as well as between net capital creation/saving and GDP growth, means that any complications of calculating capital consumption/depreciation can be avoided. Analysing first the linear correlation of gross saving and economic growth this is shown in Figure 14. This correlation of 0.84 is extremely high.

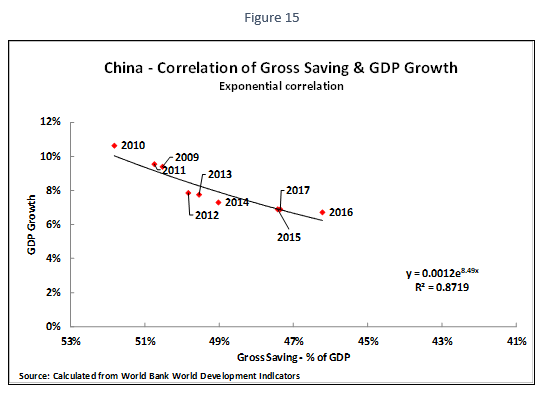

However, as already noted there is no necessity for a correlation to be linear. Figure 15 shows that the non-linear correlation is of gross saving and 0.87– an extraordinarily high correlation. As before the caveat that correlation does not establish causation is irrelevant as the extremely high correlation shows that it is not possible to increase China’s GDP growth without increasing the percentage of gross saving in GDP – and that any decline in the percentage of gross saving in GDP will be accompanied by an economic slowdown.

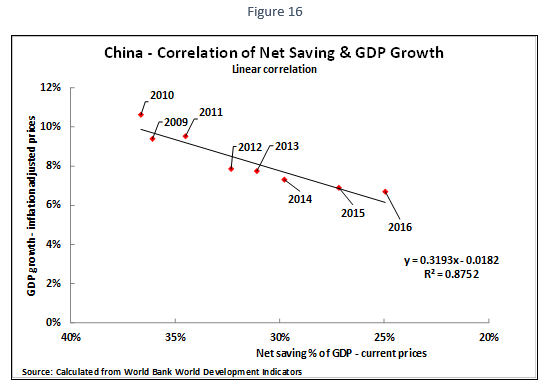

Turning to net saving, Figure 16 shows that the linear correlation of the percentage of net saving in China’s GDP with its economic growth is 0.88 – an ultra-close connection.

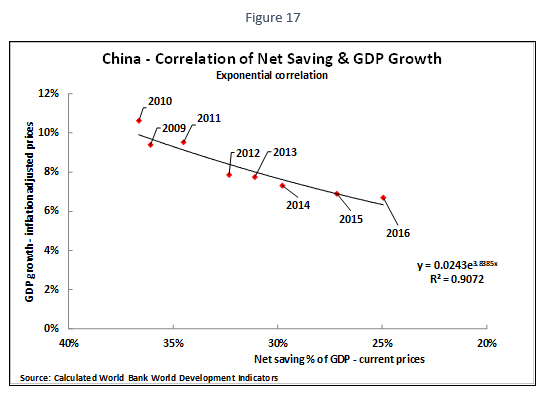

Turning to the non-linear correlation of the percentage of net saving in China’s GDP and its economic growth Figure 17 shows that this is 0.91 – an extraordinarily high correlation.

Once again the usual caveat that correlation does not establish causation is irrelevant as this extremely high correlation shows that it is not possible to increase China’s GDP growth without increasing the percentage of net saving in GDP, and that any decline in the percentage of net saving in GDP will be accompanied by an economic slowdown.

Capital creation and China’s economic growth

As it may be seen that the correlation between China’s capital creating/savings and economic growth is even closer than between net fixed investment and economic growth, it may be asked why this is the case?

This difference is not of crucial importance for economic policy, as both correlations are extremely high, confirming that it is capital creation which is the dominant issue in China’s economic growth. But it may be noted that China’s total supply of capital, measured by capital creation/savings affects other features of the economy than fixed investment. For example, a reduction in capital creation will necessarily produce negative consequences in specific markets – upward pressure on interest rates, decreasing profitability of companies, increase in leverage due to the fall in company profitability etc. These other negative effects of the fall in capital creation/saving may explain why the correlation of this with China’s economic growth is even stronger than the relation to fixed investment.

Conclusion

As emphasised at the beginning of this article there is no ‘deep crisis’ in China’s economy – China’s per capita GDP growth continues to be the fastest of any major economy in the world. This is the crucial international framework to understand. Within that overall perspective the conclusion of both modern growth accounting and national accounts measures regarding why China’s economy has slowed are the same.

-

The overwhelming cause of the slowing of China’s economy is a fall in capital/investment creation. This is shown in growth accounting by the fact that almost nine tenths of the decline in GDP growth is due to a fall in capital inputs. In national accounts data it is confirmed by the extraordinarily high correlation between net fixed investment and GDP growth of 0.81, of a correlation between gross saving and GDP growth of 0.87, and a correlation between net saving and GDP growth is 0.91 – all extraordinarily high figures.

- Demographic trends will reduce labour inputs, slowing the economy, but this effect only accounts for a small part of economic deceleration – macro-economic data shows that increased labour inputs created only a small part of China’s growth, while growth accounting shows a fall in labour inputs accounts for only about one tenth of the slowing of China’s economy.

- Growth accounting data shows that China’s TFP growth is high in terms of international comparisons – meaning it is very unlikely that China’s GDP growth can be accelerated by an increase in TFP, but that measures will have to be taken to ensure China’s TFP growth does not fall.

It is necessary to be aware of the full scale of this negative supply side shock in terms of capital creation. The decline in China’s net fixed capital investment is 9% of GDP on World Bank data. Even if the statistics on capital depreciation merit further evaluation, given their extremely high level by international standards, even measures of gross savings, which do not rely on calculation of depreciation, has fallen by 5.0% of GDP. Either figure is a severe negative supply side shock – confirming the growth accounting data which shows a sharp fall in capital inputs.

To return to the beginning of this article, the focus here is on medium/long term factors in China’s economic development. This is not contradictory to a shorter-term emphasis on demand management or supply side measures already taken to close excess capacity. However, to note again, measures affecting the demand side of the economy must necessarily operate through their impact on the supply side i.e. to produce changes in economic growth demand must create changes in labour inputs, capital inputs or TFP. Changes in demand which do not affect the supply side inputs may produce inflation or deflation, but do not produce changes in economic growth.

The consequences of this factual situation of the weight of factors in China’s economic development for economic policy are clear. As for reasons already stated TFP will be at best neutral, and demographic trends will be moderately negative, the only key input which can positively influence China’s growth rate is the level of capital inputs. This means that policies which affect capital inputs into China’s economy, that is investment, can have a powerful effect in lowering, sustaining or raising China’s economic growth rate.

This quantitative situation therefore also necessarily determines the practical efficacy of measures designed to limit China’s economic slowdown and/or to carry out any economic stimulus.

- Measures to maintain or increase market efficiency are important to try to sustain China’s rate of TFP growth but they not quantitatively able to prevent an economic slowdown – for the reasons given it is extremely improbable China could increase its level of TFP growth given its present high level. Furthermore, a strategy, which is sometimes proposed that China should allow its economy to slow but increase its TFP growth will not work for the quantitative reasons outlined – TFP growth is pro-cyclical and therefore a slowdown in economic growth will lead to a slowing of the TFP growth.

- Demand side measures to increase consumption will only be successful, for the reasons already outlined, if they produce changes on the supply side – that is, primarily if they affect capital inputs.

- Measures to cut company taxation are useful in maintaining employment and other goals but for the quantitative reasons analysed above they will only translate into faster economic growth if they lead to an increase in capital inputs – that is investment.

- In summary, given the quantitative situation analysed with demography/labour inputs and TFP, only measures which directly increase capital inputs, that is either state or private investment, will be significantly beneficial to the economic growth rate.

Practical application of policy will necessarily confirm the trends analysed. While measures such as increases in the retirement/pension age, and increases in training and education, may decrease the negative effect of demographic changes no significant body of opinion believes that a significant increase in China’s growth rate can take place due to an increase in labour inputs. There are those who argue that China’s growth could be increased due to an increase in TFP, but for the quantitative reasons given this will not be successful. For quantitative reasons the only method that will stabilise/increase growth will be an increase in capital inputs.

Postscript

This article was written to analyse in detail the slowing of China’s economy in the latter part of 2018. But its conclusion, that it is the level of investment which controls the rate of growth of China’s economy, applies equally to the good results for the first quarter of 2019. The fall in investment in 2018 led to economic slowing, the rise in investment in the first quarter of 2019 led to stabilisation in GDP growth and acceleration in other economic measures. Therefore, from both angles the data fully factually confirms that it is fixed investment which is the most powerful factor affecting China’s speed of economic development.

Appendix

This appendix is intended for economic specialists – non-specialists should know that it does not add to the main conclusions of the article. It merely indicates further substantiating evidence and explanations regarding the points in the article.

First regarding growth accounting, it is important to note the official improvements in the methods of measuring economic growth and its causes which have been formally adopted by the UN, OECD, and other statistical agencies – it is a serious problem in some literature in China that methods of measuring economic growth and its causes which are no longer accepted are used. The reasons for these changes in the official methods of calculating economic growth and its causes are analysed in detail in 为何联合国、经合组织与美国正式改变其经济增长成因测算方法? (The Copernican Revolution in Analysis of Economic Growth is Very Significant for China). But the clearest fundamental error which had to be corrected compared to former methods of analysing the causes of economic growth was that these did not calculate changes in the quality of capital and labour inputs. This meant in the case of labour, for example, that one hour of work by a South Korean peasant in 1953, who may have been illiterate, was calculated as equivalent to 1 hour of work by a South Korean engineering PhD, and very rapidly depreciating assets such as ICT equipment were not treated differently from assets which depreciated over very long periods of time. These errors are corrected in the new internationally approved methods of calculating the causes of economic growth by:

- Calculating separately labour quantity (the number of hours worked) from labour quality (the skill, educational etc qualification of labour);

- Using the category of ‘capital services’ to measure the contribution of different types of capital investments (in the OECD methodology eight categories of capital assets are used ‘computer hardware, telecommunications equipment, transport equipment, other machinery and equipment and weapons systems, non-residential construction, computer software and databases, research and development and other intellectual property products.’

In this article data calculated according to these new and approved methods of calculation are used. Regarding the correlation of GDP growth and TFP growth the correlations for single years was shown in the article. However, it is useful and important to show that the same correlation exists over not merely the short but the medium term. Figure 18 therefore shows a three-year moving average for the correlation of TFP and GDP growth and Figure 19 shows a five-year moving average. The three-year correlation is 0.81 and the five-year correlation is also 0.81. Both correlations are extremely high. The caveat that correlation does not establish causation is irrelevant as this extremely high correlation shows that it is not possible to increase China’s TFP growth while reducing China’s rate of GDP growth – that is a strategy of ‘lower GDP growth and higher TFP growth’ will not work.

This finding for China is entirely in line with international experience. In order to avoid overburdening the text with detail for non-specialists only the 2018 OECD finding was cited. However, this is entirely in line with all OECD studies on the issue. To show this reference to the previous OECD studies are therefore given here.

In 2012 the Compendium of Productivity Indicators noted: ‘the empirical evidence confirms the pro-cyclical pattern of MFP. In fact, MFP follows GDP growth very closely, not only in terms of the direction but also the size of the change.’ (OECD, Compendium of Productivity Indicators 2012 p11.) And therefore ‘MFP behaves cyclically, i.e., it increases in an upturn and declines in a downturn.’ (OECD, Compendium of Productivity Indicators 2012 p58.)

The 2013 Compendium of Productivity Indicators had the same finding: ‘multifactor productivity growth (MFP) behaves cyclical, i.e., it increases in an upturn and declines in a downturn. ‘ (OECD, Compendium of Productivity Indicators 2013 p62).And: ‘The empirical evidence confirms the cyclical pattern of MFP. In fact, MFP follows GDP growth very closely, not only in terms of the direction but also in terms of the size of the change. ‘ (OECD, Compendium of Productivity Indicators 2013 p62)

The 2015 Compendium of Productivity Indicators similarly concludes: ‘MFP appears to have moved in a pro-cyclical way’ (p30) And: ‘multifactor productivity growth (MFP) behaves cyclically, i.e. it increases in an upturn and declines in a downturn.’ (OECD, Compendium of Productivity Indicators 2015 p64)

The 2016 report notes ‘The empirical evidence points to the recent slowdown in labour productivity being in at least in part explained by its pro-cyclical pattern, particularly for MFP’ (OECD, Compendium of Productivity Indicators 2016, Kindle Location 61) And: ‘multifactor productivity growth (MFP) behaves cyclically, i.e., it increases in upturns and declines in downturns.’ OECD, Compendium of Productivity Indicators 2016 (Kindle Location 1704-1705).

The 2017 OECD report again finds: ‘multifactor productivity growth (MFP) behaves cyclically.’ (OECD, Compendium of Productivity Indicators 2016 (Kindle Location 1704-1705).And that: ‘The empirical evidence confirms the cyclical pattern of MFP. In fact, MFP follows GDP growth very closely, not only in terms of the direction but also in terms of the size of the change.’ (OECD, Compendium of Productivity Indicators 2017 (Kindle Location 1532).

The OECD’s factual finding is therefore clear and unequivocal. Slowing of GDP growth leads to a slowing of TFP growth. A strategy of ‘slower growth to achieve higher TFP increases’, other things being equal, therefore won’t be successful – a slowing of GDP growth will be associated with slower TFP growth.

* * *

This article was previously published on Learning from China and originally in Chinese at Guancha.cn.

Recent Comments